MIND THE GAP!

The Western Ghats in southern India is a chain of mountains

running along the western coast of the Indian peninsula for about 1,600 kms.

The Ghats have for long been considered as a global biodiversity hotspot (Myers

et

al. 2000),

and also features in the list of UNESCO world heritage sites. The Ghats are

non-contiguous and have a varying elevation owing to which there are numerous

wide and deep valleys that form along the length of mountain range. This fragmentation

is responsible for the formation of continental islands (sky islands) that can

be defined as a, ‘continental or inland terrain made up of a sequence of

valleys and mountains,’ (Warshall 1994). The Western

Ghats Mountains in southern India harbor one such tropical sky island system (Warshall 1994) that consist a mosaic of high elevation montane

temperate, evergreen forests ( OR ‘Sholas’ as they are locally called) and

montane grasslands. The Shola forests have been known to host a great deal of

endemic birdlife and are considered as models to study the evolution of species

from an ancestral distributional range.

The hills of Kalakad Mundunthurai Tiger reserve (Western Ghats), south of the Shencottah gap.

Mosaic of Shola forests and grasslands in the sky islands.

The white-bellied shortwing, considered to be a rare

species until recently, is a globally threatened (Vulnerable B1+2a,b,c,d,e; BirdLife

International 2001), passerine, understory bird endemic to the Western Ghats of India (Collar et al.

2001). There are five species of shortwing found in

the Indian Subcontinent of which three are found in the North East and two are

endemic to the Ghats. The White bellied shortwing is found uniquely in the Shola forests at

elevations of 1500 msl and above on the sky island systems of the Western Ghats (Robin & Sukumar

2002; Robin et al. 2006). These birds are specialists in terms of their habitat

preferences and slight changes in their habitat can affect their populations. Once reported to be

fairly common (Ali and Ripley 1987), there have been only a few records lately.

Rufous bellied shortwing (©Clement Francis)

White bellied Shortwing (©Bopanna Pattada)

The most likely causes of the

decline in population can be attributed to loss of its montane evergreen

habitat, continuing habitat fragmentation and degradation (Birdlife

International 2001). It is estimated that the Western Ghats

has lost about 25.6% of the forest cover in the last two decades (Jha C. 2010)

Fragmentation in these

mountain ranges occurs on three levels, firstly on a larger, geographical level

with wide and deep valleys serving as biological barriers that prevent

dispersal of individuals. Second, the mosaic of montane grasslands and high

elevation shola forests and lastly, fragmentation as a result of anthropogenic

effects have all contributed to the formation of allopatric populations that

are genetically isolated on these ‘sky islands’.

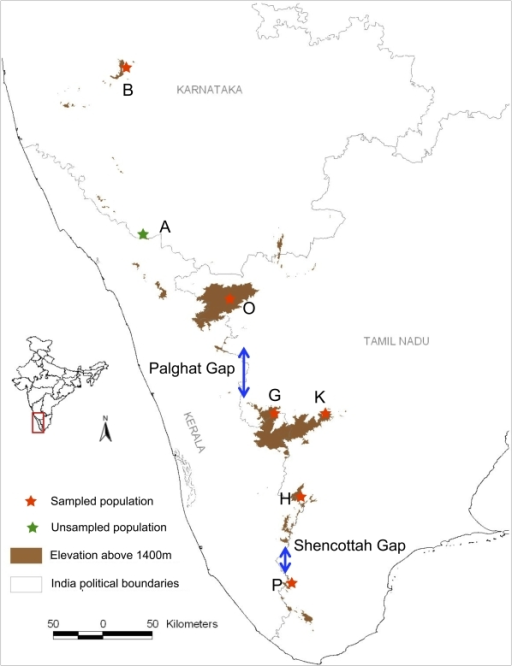

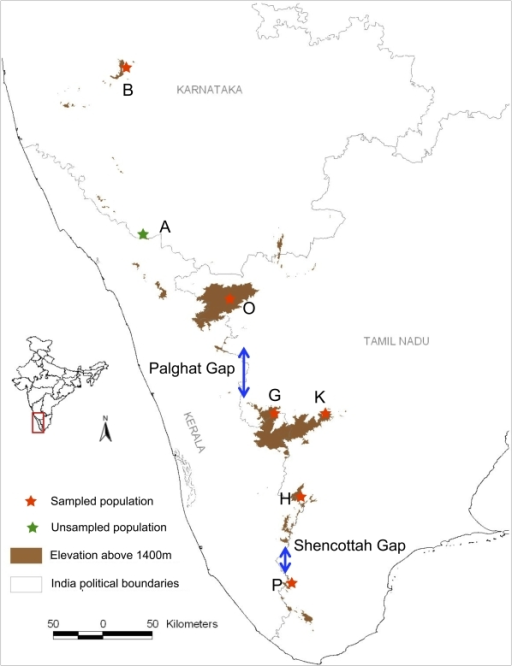

Palaeoendemics such as Shortwings; which prefer a specialist

paleoclimate and geography are affected by the deep valleys of the Palghat and Shencottah

gaps (Robin et

al. 2010). The Western Ghats

are an ancient mountain system with the largest geographical gap, the

c. 40 km wide Palghat Gap serving as the major biological barrier,

and the smaller Shencottah Gap, further south acting as a barrier on a smaller

magnitude. The topography of the Western Ghats is relatively very old, having taken

shape about 65 million years ago (Ma) (Gunnell et al. 2003). This

indicates that the geographical conditions and paleoclimate was conducive for

colonization of the mountains by passerine birds much before they actually

arrived on the evolutionary scene 50-60 million years ago. The White-bellied

Shortwing exhibits high population genetic divergence across islands, with

populations on a single island being genetically similar, although ecologically

isolated (Robin

et al. 2010). Populations that inhabited islands across larger valleys such as

the Palaghat Gap were found to exhibit far greater genetic divergence when

compared to individuals across the smaller valleys. The evidence points to a

pattern of colonization by these birds with two probable strategies of

colonization. Ancestral individuals could have first arrived at the foothills

and gradually moved up the mountains as paleoclimate varied as a result of

which sightings have been mainly restricted to above 1500 mts. Another theory postulates

that ancestral individuals initially colonized the first island in the sky

island system and gradually hopped across islands to colonize them, as a result

of which, hypothetically the oldest ancestors should be on the first island in

the system.

Map showing the location of the Palaghat Gap and the Shencottah Gap (Source: V.V. Robin)

Map showing the location of the Palaghat Gap and the Shencottah Gap (Source: V.V. Robin)

On examining the effects of genetic differentiation across

populations of the white-bellied shortwing, (Brachypteryx

major), on different islands of this sky island system it was observed

that individuals separated by the larger, 500-million-year-old geographical

genetic gap- the Palaghat Gap, were found to be genetically different from

those on islands separated by smaller valleys. Genetic analysis showed

significant variations in combined mitochondrial DNA genes (cytochrome b,

cytochrome oxidase 1 and control region).

However populations from Grasshills and Kodaikanal showed little genetic

differentiation using the same molecular markers. (Robin et al. 2010). ). It

was also observed that although all three populations have similar habitat

structure characterized by stunted montane evergreen Shola forests (described

in Meher-Homji 1984; Shanker & Sukumar 1999), geographical isolation had

lead to phylogenetic divergence over time. As a result of this divergence, two

newly discovered subspecies, B. m. major and B.

m. albiventris,

separated by a geographical gap in the Western Ghats (Palaghat gap), with the former

and latter distributed to the north and south of the gap respectively (Robin et

al. 2013) were identified. Using molecular methods of sequence analysis the

White-belied Shortwing was split into two subspecies, the White-bellied

Shortwing, and the Rufous-bellied Shortwing. Ongoing research has provided

evidence for the existence of a nest basket effect wherein deep and wide

valleys serve as drivers for phylogeographic divergence, with the oldest divergences

exhibited by the Palaghat Gap, while the younger divergences were seen in the

Shencottah Gap and the Chaliyar valley.

However certain species failed to exhibit a pattern of divergence for which four probable patterns have been suggested. (i). Ability of species to actively disperse across these barriers, (ii). Extinction and recolonization responses to paleoclimatic changes, (iii). Incomplete lineage sorting owing to recent divergence, (iv). recolonization during inter-glacial periods where conditions at lower altitudes were warmer compared to cooler climates at high elevations. (Robin, Vishnudas Ck, Pooja Gupta. 2015). Various inter-related factors therefore have been found to influence divergence amongst endemic birds of the sky islands. Topographical variations of the valleys, deep and wide valleys and paleoclimatic conditions have been found to serve as drivers for divergence. Further research is required to assess which of these factors impact individual species, either singly or in combination to help serve as drivers for divergence. There is a need to assess if this pattern of divergence is restricted to highly endemic specialists, or if patterns of divergence and the nest basket effect hold true for species exhibiting a broader distributional range. The outcome of such a study would be a complete phylogenetic map to the endemic birds of the Western Ghats, if not one for all the birds of the Western Ghats. This would enable detection of variations amongst inhabitants on either side of the Gaps and assess whether sub-species have been hiding in plain sight. Use of advanced molecular methods of sequencing can provide evidence for the existence of any such divergences that may not have previously been looked into. Assessment of the age of the phylogenetic divergence can serve to establish whether allopatric populations alone exhibit divergences over time or if species that have successfully colonized these sky islands before the arrival of the shortwing also exhibit divergences as a result of these geographical, genetic barriers which are ancient in their origin.

References:

i. A view from the past: shortwings and sky islands

i. A view from the past: shortwings and sky islands

of the Western Ghats – Robin

V V, A. Sinha & U. Ramakrishnan, Indian Birds Vol.

7 No. 2 30 (Publ. 15 October 2011)

ii. Ancient Geographical

Gaps and Paleo-Climate Shape the Phylogeography of an Endemic Bird in the Sky

Islands of Southern India- V V Robin, A Sinha, U Ramakrishnan- PLOS One · 2013 October

iii. Deep

and wide valleys drive nested phylogeographic patterns across a montane bird

community, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences · July

2015

iv. Determining the sex of a monomorphic threatened, endemic passerine in the

sky islands of southern India using molecular and morphometric methods, V. V.

Robin , Anindya Sinha,

Uma

Ramakrishnan- Current Science · September

2011

v. Islands within islands: two montane

palaeo-endemic birds impacted by recent anthropogenic fragmentation -ROBIN. V. V , Gupta. P

et al - Molecular Ecology ∙ July 2015

vi. Singing in the sky:

song variation in an endemic bird on the sky islands of

southern India

V. V. Robin, Madhusudan Katti et al, January

2013, Rare Animals of India

vii. Status and distribution of the Whitebellied Shortwing (Brachypteryx major) in the Western Ghats of Karnataka and Goa, India- Bird Conservation International · December 2006

***********************

No comments:

Post a Comment