Isolated but not alone?

The "Sahayadris" as they are locally known are the largest range of mountains in Southern India. The Ghats run through seven states in the southern peninsula- Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu and finally ending at Kanyakumari, the southernmost tip of India (Vijayan, V.S, 2007). These hills run for over 160,000 sq kms before and are responsible for the south west monsoons. The mountains block the rain clouds that come across from the Arabian Sea and it is this yearly phenomenon that is responsible for the formation of seasonal streams.

The Western Ghats of India, a biodiversity hotspot and a UNESCO world heritage site.

This area is one of the world's ten "Hottest biodiversity hotspots" containing over 7,402 species of flowering plants, 139 species of mammals, 508 bird species, 1,814 species of non-flowering plants, 179 amphibian species, 6,000 insects species and 290 freshwater fish species. It is estimated that over 325 threatened species call these Ghat ranges home. There is also a high possibility that species may still lie undiscovered and some may even be hiding in plain sight. There are 16 species of birds that are considered extremely endemic to this mountain range and can be found nowhere else in the world. They are, the Nilgiri Woodpigeon, Malabar Parakeet, Malabar Grey Hornbill, White-bellied Treepie, Grey-headed Bulbul, Broad-tailed Grassbird, Rufous Babbler, Wynaad Laughingthrush, White faced Laughingthrush, Grey Faced Laughingthrush, White bellied Shortwing, Black-and-rufous Flycatcher, Nilgiri Flycatcher, White-bellied Blue-flycatcher, Crimson-backed Sunbird and the Nilgiri Pipit.

White-Bellied-Blue-Flycatcher

Malabar Trogon male, another endemic of the Western Ghats.

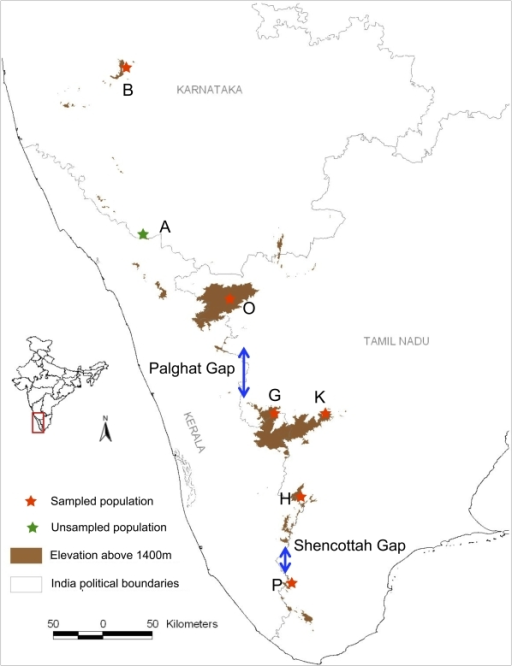

With specific habitat preferences being exhibited, these birds are extremely selective in the types of habitats that they choose to utilize. It is this specialization that behaves as a driver to induce genetic variations among populations. The Western Ghats are non-contiguous with three prominent gaps occurring along the length of the mountain range, the Palaghat Gap, the Shencottah and the Chaliyar valley. These gaps, coupled with the various other geographical, climatic, physical, altitudinal barriers, etc lead to species remaining isolated from larger populations over time. Such populations are deemed “Allopatric Populations” which are separated from a larger population of related individuals by a geographical barrier.

Research has shown that isolation and genetic drift is responsible for variations in song patterns of endemic songbirds (Robin. 2010), this proves that genetic drift is seen to occur across populations, including those that aren’t isolated.

Observations amongst birds of the Ghats from either side of these prominent gaps show that there is a variation in the song as well as pitch of the calls. Individuals from both sides also exhibit subtle plumage variations in a small number of cases. On a molecular level however, using what geneticists refer to as Ultraconserved elements Or UCE (Gil Bejerano et al. (2004), which are sequences in the genome that are highly conserved amongst evolutionary distant taxa. Utilizing specific sequence capture probes, one can sequence the genome of these fragments and post alignment based on homology; obtain a clearer picture of the entire genome sequence of the organism. Since these UCE’s are extremely conserved in their positions at specific loci on the genome, subtle variations between sequences of individuals of the same species will provide researchers with evidence for allopatric speciation amongst specialist endemics. However, till date researchers have made use of microsatellite DNA variations as well as variations among nuclear genes as evidence to point towards phylogenetic splits. URE’s have yet to find their footing in molecular biology studies.

What would be interesting though would be to study the variations in the genomes of endemic birds across gaps as well as non-endemics and check if a pattern emerges, with a particular threshold distance to qualify as geographical genetic barriers. Endemics, owing to their specialist nature do not disperse as readily as generalists, this pattern should be evident in the genomes with allopatric endemic individuals exhibiting larger variations among the URE’s across the gaps and generalists exhibiting fewer variations among the URE’s. Theoretically, even among endemic individuals that are found throughout the Ghats as opposed to those found only in certain localities, variations should be seen in the genomes. This opens up a Pandora’s Box of questions for taxonomists and biologists alike. Have we missed reading the fine print? Are there species hiding in plain sight? Do widespread endemics also experience the effects of allopatric speciation to the same extent as their specialist compatriots?

References:

1. Nayar, T.S.; Rasiya Beegam, A; Sibi, M. (2014). Flowering Plants of the Western Ghats, India (2 Volumes). Thiruvananthapuram, India: Jawaharlal Nehru Tropical Botanic Garden and Research Institute. p.1700.

2. Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Fonseca, G.A.B.Da; Kent, J. (2000). "Biodiversity Hotspots for Conservation Priorities". Nature. 403: 853–858.doi:10.1038/35002501. PMID 10706275.

3. "The Peninsula". Asia-Pacific Mountain Network. 2007.

4.Vijayan, V.S. "Research needs for the Western Ghats" Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE). Retrieved 21 June 2007.